A quick update on what I’ve been doing, reading, spending my time with, etc! You’d have thought that being off school this summer would have given me lots of writing time, but that does not appear to be the case! I did do a lot of reading this summer, though, as well as thinking about lots of tweaks for my classes. We start on Thursday and I’ve very excited. I’ve also spent some time thinking about social media and my interaction (or lack thereof) of it. I’ve pretty much tacitly given up Facebook; my account is still there and I check in a couple of times a month. I’ve cleaned up my Twitter follows a bit and am tentatively dipping back in there (I do refuse to call it X, sorry). I’ve also been spending quite a bit of time on Micro.blog. I actually use it for the timeline, and haven’t done a lot to make the blog landing page nice, but if you ARE on Micro.blog and use the timeline/social aspect, I would love to see you there.

Links from Elsewhere

What I’ve been reading and thinking about lately. Lots about education (especially classical education) but also books, film, games, etc. Also note that in my small attempt to push back on the internet’s recency bias, I will not hesitate to post older articles if they are still interesting and relevant.

Assessments That Aim for Real Knowledge – Circe Institute

For the first time this year, I’m planning to go completely without multiple choice/short answer/fill in the blank/matching/etc type quizzes. I’ve never used them heavily because when I have used them (mostly as reading quizzes or vocab quizzes) I always feel wrong about them, for all the reasons suggested here. I’ve fallen back on them because I felt like I had to have some, for some reason, but this year, no more.

Some things have to be memorized, but one of the most difficult habits I’ve had to break is giving tests that rely too heavily on memorized bits of data. These kinds of tests are mostly matching, multiple choice, or fill-in-the-blank questions, often with a token essay question at the end. Since the goal of a test is to assess knowledge, I’ve had to reconsider what it means to really know something, and I’ve discovered there is a significant difference between knowing and memorizing facts.

Oppenheimer Doesn’t Show Us Hiroshima and Nagasaki; That’s an Act of Rigor Not Erasure – LA Times

I don’t spend a lot of time looking at hot takes these days, for which my life is infinitely better, but this article addressing a specific hot take on Oppenheimer came across my feed and the general idea here is very important. Not every story has to be about everything, and not every film has to show every aspect of the story it is telling. If the argument is that people get their history from the movies, my answer is that it is not an artist’s job to make up for your terrible education. Reading this is also the most interested I’ve been so far in seeing Oppenheimer.

Movies that attempt something different, that recognize that less can indeed be more, are thus easily taken to task. “It’s so subjective!” and “It omits a crucial P.O.V.!” are assumed to be substantive criticisms rather than essentially value-neutral statements. We are sometimes told, in matters of art and storytelling, that depiction is not endorsement; we are not reminded nearly as often that omission is not erasure. But because viewers of course cannot be trusted to know any history or muster any empathy on their own — and if anything unites those who criticize “Oppenheimer” on representational grounds, it’s their reflexive assumption of the audience’s stupidity — anything that isn’t explicitly shown onscreen is denigrated as a dodge or an oversight, rather than a carefully considered decision.

How I Take Notes – The Honest Broker (Ted Gioia)

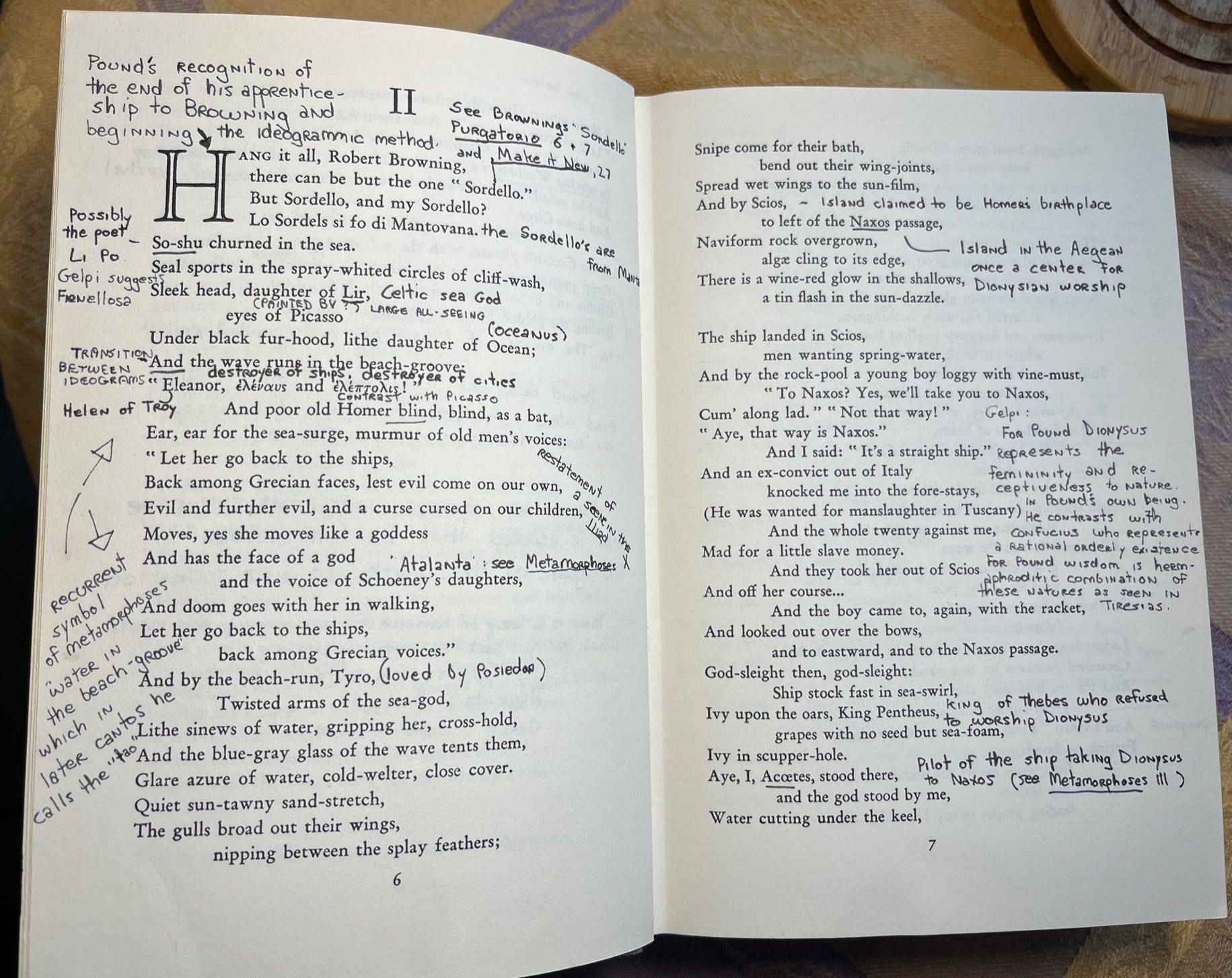

No joke, Ted Gioia’s Substack is probably the best thing I read on a regular basis these days. He frequently talks about music or the music business, since that is his main focus, and those posts are great and thoughtful. He also frequently writes on other topics, and these are also uniformly interesting. This time, he’s talking on a subject near and dear to my heart – note-taking! This is something we try to teach our students, and as you might expect, some seem naturally good at it and others never care enough to make it useful to them. I’m always excited to hear other people talk about how they take notes and see what I can incorporate into my own attempts to do it and to guide students in it. I personally feel like I annotate books pretty well, but I struggle with longer-form summary/narration or contemplative notes. I just rarely want to take the time to do it, even though when I do it’s been very valuable.

(3) WRITING DOWN MY OWN IDEAS THAT THE BOOK SPURRED: I didn’t start doing this with any consistency until I was approaching middle age. But this is the most powerful kind of note-taking of them all.

By doing this, I expand my own thinking by leaps and bounds. Often the notes I write in this manner serve as the building blocks for my own articles and books. But even if I wasn’t a writer, I would benefit from this—because the greatest reward from reading is in the ways it improves and broadens you as the reader.

A New Rule of Education in the Age of AI – Hedgehog Review

How to handle AI is an ongoing concern among all educators, and we’ve talked about it plenty at our school. What stood out to me in this article is the idea of rule-as-model rather than rule-as-restriction, which I think is really helpful in general! We want all of our “rules” to be formative and not merely restrictive, and this has applications far beyond rules against using AI. In that particular case, though, it’s a helpful reminder to us and students that the point of writing in school is not the product (which AI can supply) but the formative thinking that writing requires (which AI cannot).

In The Rule of St. Benedict, the abbot holds his post because he doesn’t simply know the rule; he embodies it. The abbot, in turn, exercises discretion over the application of the code to promote the good of the members of and visitors to the community. Those under the rule strive to emulate this model person—not just “the rules”—in their own lives. “Whether the model was the abbot of a monastery or the artwork of a master or even the paradigmatic problem in a mathematics textbook, it could be endlessly adapted as circumstances demanded,” Daston observes. The ultimate goal of such a rule is not to police specific jurisdictions; it is to form people so that they can the carry general principles, as well as the rule’s animating spirit, into new settings, projects, problems. We need a new Rule of Education—one that grants educators discretion and is invested in students’ formation—for the age of AI.

A World Without Turner Classic Movies – Film School Rejects

The good news here is that TCM has rehired Charlie Tabesh, but I don’t think we’re out of the woods yet. When Discovery merged with Warner Bros. and put Discovery exec David Zaslov over the whole shebang, a lot of Warner properties suffered – HBO Max has been gutted of most older programming, the staff of TCM has been reduced significantly, etc. This is very worrying for classic film fans, and while some moves (like rehiring Tabesh) suggest they may be responding to the outcry, again, I’m still worried. Losing TCM would be tragic for so many reasons. I hope my pessimism isn’t justified.

As someone who studied film in college and writes about it professionally, TCM remains the best education I’ve ever had, largely due to its accessibility. I felt terrified to make a mistake in front of film students and professors, to not know a movie I should have already seen when I was a student. Hosts like Alicia Malone and Ben Mankiewicz are knowledgeable without being condescending. All of the TCM hosts have truly felt like friends telling you about movies they love when visiting your home and that is such a treasure.

If You Love Books Play These Games – BookRiot

Board games for book lovers? Sign me up! Relatedly I apparently accidentally bought this game Gutenberg about being a print shop in the Renaissance (thankfully on a good discount!), so I’ll let you know how that is when I have a chance to play it.

A comic because why not

Reading Right Now

Recently Added to My TBR

I add books to my TBR at a far faster clip than I read them. At least I’ll never run out! These run the discovery gamut from Bookriot and Literary Hub to Medievalists.net, Circe Institute, our faculty inspiration speaker last week, and recommendations from personal friends.

Watching

We recently went to the Santa Barbara Mission and they had a special exhibit about the Sistine Chapel, which was very cool for my art-loving older daughter. She took her time studying and reading about all the panel reproductions, while the rest of us watched this video they had playing three times. This channel got an insta-subscribe when I had service back on my phone.

Listening

I’ve decided to try to spend more time pretending I have actual albums instead of Spotify, because the loss of mastery I used to have when I listened to the same album over and over is leaving me unmoored. This is an older Metric album, though still from after the time I considered myself a major fan. I went back and listened to it a couple of times today and…it’s really good.