March’s featured collections on the Criterion Channel were a treasure trove for me! I was quite interested in almost all of them, but I had to focus on just a couple. First up had to be the Paramount Pre-Codes. I’m generally a pretty big fan of Pre-Code Hollywood, and unsurprisingly I had seen about half of this collection already.

If you’re new to Pre-Codes, I can’t recommend Trouble in Paradise, Love Me Tonight, and Shanghai Express enough. Those three should definitely be top priority if you haven’t seen them (they should be on the channel through at least the end of April – I forget whether they keep collections on for two or three months). I also really enjoy the other three I had seen: The Smiling Lieutenant, She Done Him Wrong, Design for Living, and One Hour With You.

This left largely obscurities for me to see, though some big names are attached to those obscurities – like a very early Cary Grant film, a couple of Dorothy Arzner-directed films (the only female director working in Hollywood in the 1930s), and an omnibus film with sections directed by Ernst Lubitsch among others. As of April 1, there are still a couple of films I haven’t gotten to – the 1934 Cecil B. DeMille version of Cleopatra, and the Ernst Lubitsch-directed drama Broken Lullaby. The former should be fairly easy to find and watch, and I have less interest in Lubitsch directing drama, though I should watch it for completionism’s sake. Maybe sometime this month.

Night After Night (1932)

A nightclub story, with the gangster activity and love affairs you might expect from that. Raft’s character has a girl, but becomes enamored of a glamorous woman who comes in alone frequently – turns out his club is built in the mansion she grew up in, and she’s sentimental. She’s clearly of a higher social caliber than he is (he is taking lessons in etiquette and general knowledge to move up the social ladder) and he falls hard for her. Meanwhile, a former lover turns up – Mae West in her film debut. She steals the show, but the rest isn’t bad either. However, it’s not going to make you a fan of this type of movie if you’re not already. It has some amount of early sound clunkiness.

Merrily We Go to Hell (1932)

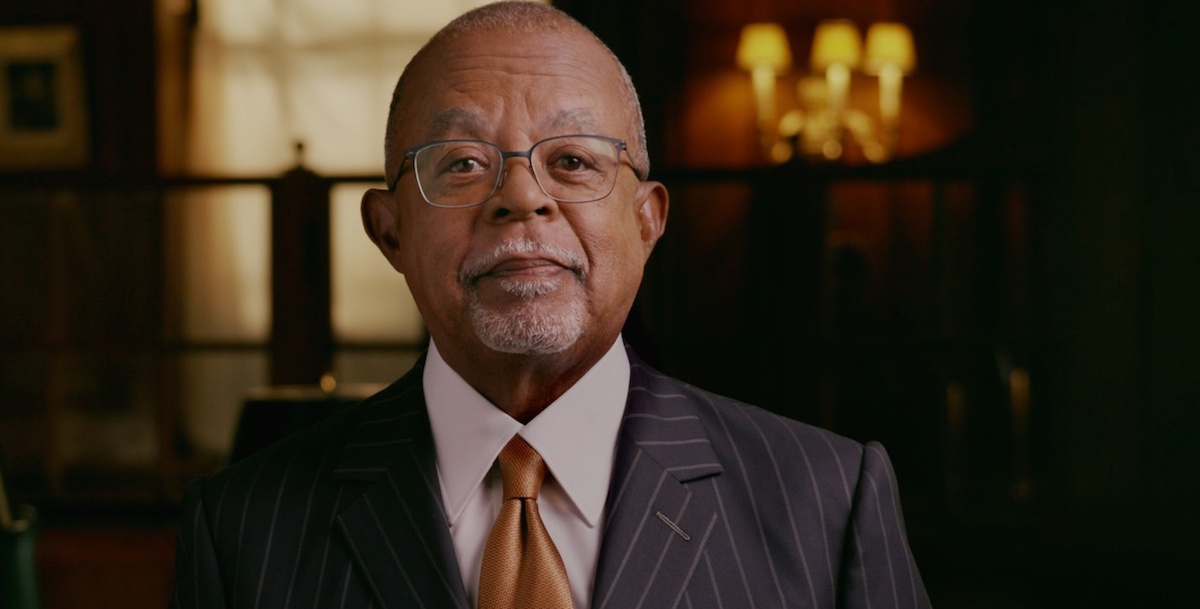

One of the two Dorothy Arzner-directed films in the featured collection, Merrily We Go to Hell focuses on a star-crossed couple – Jerry (Fredric March), a reporter and would-be playwright, and Joan (Sylvia Sidney), an heiress who falls for him against her family’s wishes. Their relationship is rocky to say the least – she stands by him in good times, as when his play gets produced, and less-good ones, as when he missed their engagement party because he freaked out and got drunk. Until, that is, Jerry falls into seeing his old girlfriend, now a famous actress, and Joan decides to have a fully “modern marriage” – that is, basically an open, swinging marriage where each of them can do whatever they want on the side. (Look for a young Cary Grant here as one of her “on the sides”.) There’s a very thoughtful and mature tone throughout all these shenanigans, which could easily have just been played for laughs or crudity. I was impressed with how well this story was handled. Props to Arzner, for sure.

Honor Among Lovers (1931)

This is the other Arzner film, with Claudette Colbert as the greatest ever executive assistant plus a super great person in general, so it’s not super surprising that her boss Fredric March falls in love with her. She’s not keen on a potential office romance, though, so she quickly marries her existing boyfriend, an up-and-coming stockbroker. They’re pretty happy for a while, but stockbroker boy is speculating pretty heavily with other people’s money and things go downhill from there. There are a lot of interesting and unusual plot moves made here, and while I didn’t love all of them (having the initially lascivious March become the “good guy” was a bit hard to swallow), it was an enjoyable ride, and Colbert is never less than luminous. Also look for a really young Ginger Rogers as a complete ditz. Sort of an unfortunate part, but there you go.

If I Had a Million (1932)

A dying millionaire is fed up with all of his money-grubbing potential heirs and decides to give a million dollars each to eight strangers chosen at random from the telephone book. We then see eight vignettes (each directed by a different director – Ernst Lubitsch, Norman Taurog, Norman Z. McLeod, etc) that show what each of the recipients did with the money. As usual with these kinds of omnibus films, the stories range from the heartwarming to the sad to the ridiculous. None of these are particularly great as omnibus segments go, but none of them wear out their welcome too much, either.